The Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder’s (CEWH) Science Program funds the Flow Monitoring, Evaluation and Research (Flow–MER).

We acknowledge the Gomeroi/ Gamilaroi/ Kamilaroi/ Gamilaraay Peoples, the Traditional Owners of the Guwayda (Gwydir) River and surrounds. Thank you for sharing your Country and knowledge of the land, water and life with us. We pay respects to Elders past and present.

Traditional Gamilaaraay Language of the Gomeroi Nation used in this article (H. White & B. Duncan – Speaking Our Way, M. Mckemney), enhanced through working with community members and Kerrie Saunders and Liz Taylor the Guwayda (Gwydir) River Selected Areas Cultural Advisors.

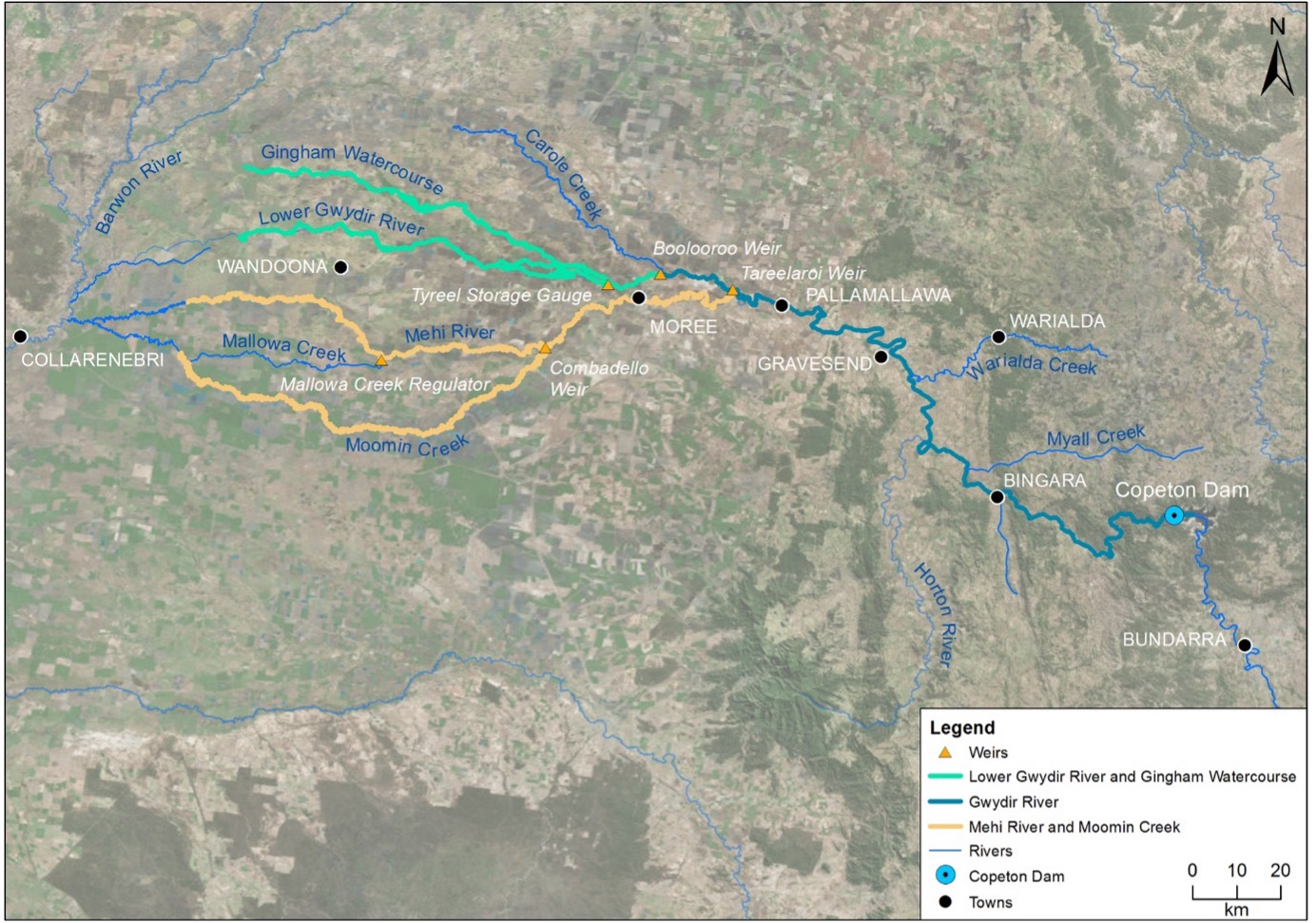

For the last decade the CEWH has funded river and wetland monitoring and research in the Guwayda (Gwydir) Wetlands and catchment (Figure 1). This work is part of the larger Flow – Monitoring, Evaluation and Research (Flow–MER) program that spans the entire Murray-Darling Basin.

The upper catchment of the Guwayda River is described as montane, before reaching the plains near Gravesend where the floodplain begins to widen. Downstream of Moree, the system fans out into a broad alluvial near-terminal floodplain-wetland complex. This lower region consists of the Mehi River, Moomin Creek and Mallowa Creek to the south, and the Lower Guwayda River, Gingham Watercourse and Carole Creek to the north.

These channels support wetland and floodplain assets including the Lower Guwayda and Gingham Wetlands (areas of which are declared Ramsar wetlands), and the Mallowa Wetlands.

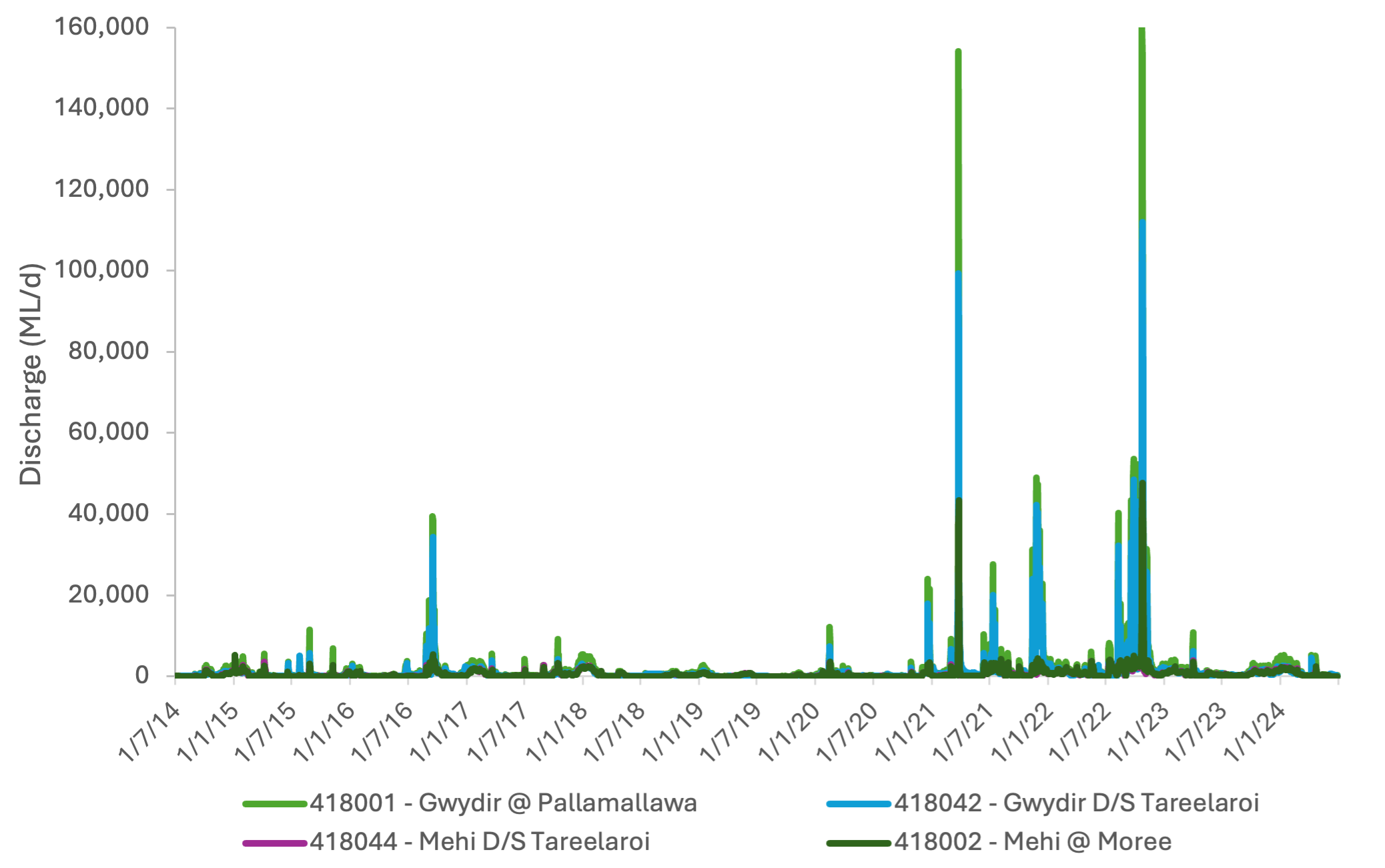

The CEWH implemented the Long-term Intervention Monitoring (LTIM; 2014-2019) and the Flow-MER (2019-2024) programs in this area to evaluate the outcomes of Commonwealth water for the environment delivery. This story explores some key learnings since monitoring began in the Gwydir Selected Area spanning times of severe drought (2018-20) to significant flood (2021-22; Figure 2).

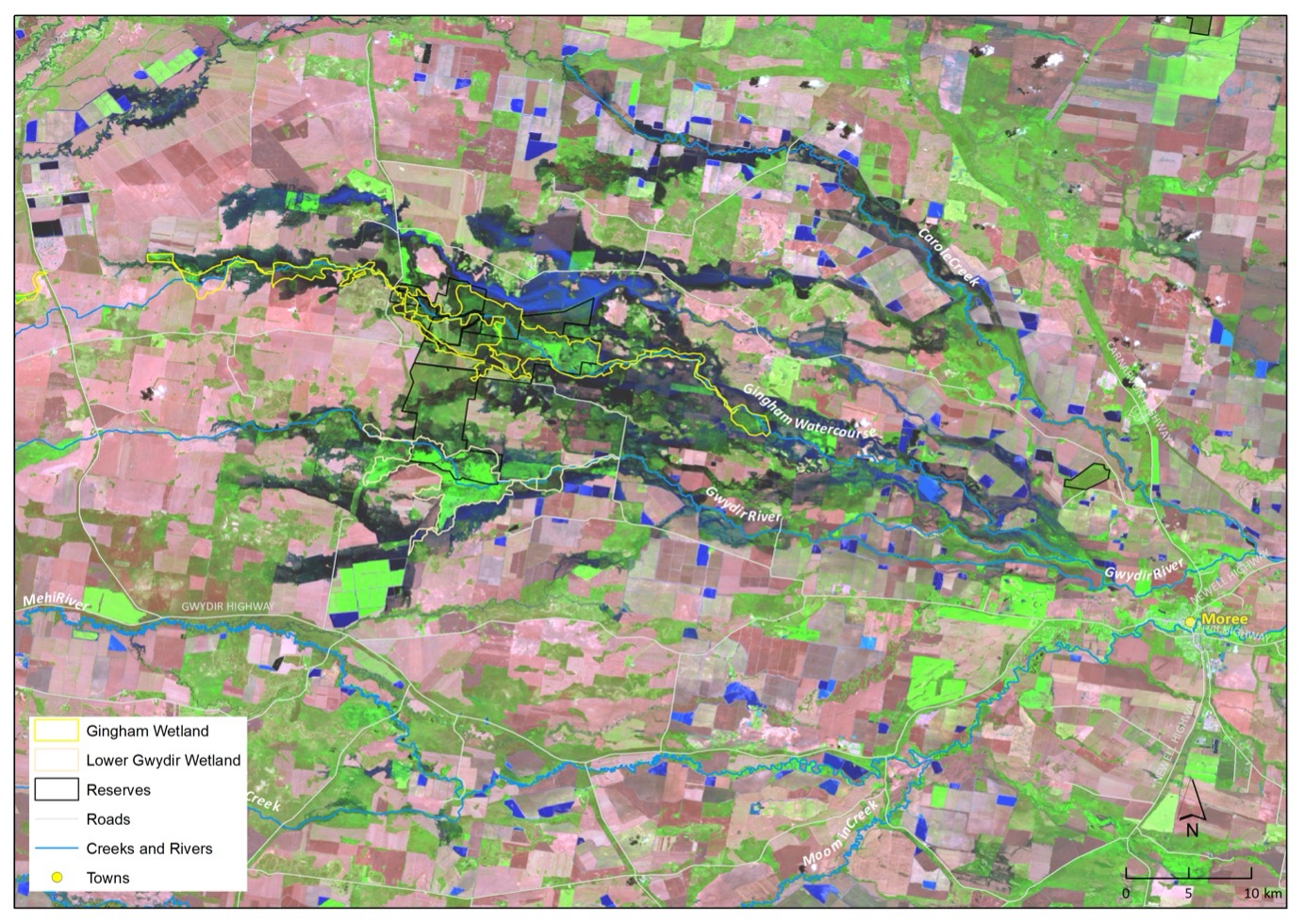

The 2014 to mid 2019 period was largely dry and large wetland areas dried back (Figure 3). During this period water for the environment played a critical role in maintaining moisture in core wetlands. Some natural flows benefitted the region in 2016-2017, with water for the environment helping flows extend to the lower Guwayda wetland areas. Wetter conditions allowed vegetation, such as lignum and water couch to re-establish. These inundation pulses also improved fish and turtle survival in waterholes (Figure 4).

Engagement with local First Nations peoples began in 2019 with collaboration on stories and has grown since then. Embracing cultural knowledge and practices is a learning process that is continuously being developed and improved. Engagement with the Gomeroi People, the Traditional Owners of the Guwayda (Gwydir) catchment and surrounds has supported this on-going process (Figure 5 and 6).

Increased natural flows in early 2020 were followed by consistent wet conditions up until 2023. During this time, Copeton Dam supplied vast quantities of water for the environment allowing for waterway connectivity. Biodiversity boomed in the transition back to a wet state, with DPI Fisheries noting improved guduu (Murray cod; Figure 7) recruitment. Additionally, prolonged wet conditions in 2021 stimulated the largest colonial waterbird nesting event in a decade (Figure 8). The Lower Gwydir and Gingham watercourse supported 14 colonial waterbird species to breed, and an estimated 45,000 nests were built between December 2021 and March 2022. December 2021 also saw the most significant inundation of the core wetland areas in this period, as shown in Figure 9. Subsequent flooding saw nesting repeated in 2022 with continued high inundation of the wetlands. During both years, water for the environment was used to maintain water levels under nests to increase the chances of breeding success. This transformation from a dry to wet landscape also saw improvements to vegetation, with water loving native species such as lignum, water couch and nardoo dominating vegetation communities (Figure 10).

Dry conditions returned in 2023. Gingham Waterhole dried up completely by early November, leaving thousands of carp and other fish carcasses. Towards the end of 2023 and into 2024, rainfall and water for the environment contributions saw some water return to the wetlands. Nevertheless, unlike in 2021-22, waterbirds were sparse. A lightning storm in March 2024 ignited a large section of the Old Dromana Ramsar site. By May, vegetation surveys found some recovery, however exotic weeds such a lippia were quickest to establish on the burnt mash club edges and elsewhere. Its expected that over time, native species will again outcompete lippa in these areas and native wetland communities will re-establish.

Overall, monitoring improved the understanding of ecological processes in the Guwayda Selected Area. This helped to inform environmental water deliveries and make them more effective in supporting the ecology of the region.

Managing water for the environment is a collective and collaborative effort, working in partnership with communities, private landholders, scientists and government agencies – these contributions are gratefully acknowledged.

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we live, work and play. We also pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging.